By Tara Adhikari

Kiona Sperr, a junior, holds up her hands next to each other and then drops her left hand so that there is a sizable gap in between. She then moves both her hands upward, but the gap between the two remains. Sperr, through these hand gestures, is illustrating her definition of systemic racism.

“There was nothing to level the playing field [after slavery was abolished],” says Sperr explaining why the gap between her top hand, representing white people, and her bottom hand, representing people of color, exists.

Sitting just a couple tables over in the socially-distanced dining hall, senior Dean Colarossi explains it differently. “I think that racism is bad,” he says. “I think there are racist people, but I don’t think it is a system by means of that word.”

These two students, who both major in economics, consider systemic racism in completely different terms. However, this difference is not uncommon. Pew Research studies from 2019 and 2020 show the United States to be divided on issues pertaining to systemic racism, such as whether Black people have equal rights and whether the legacy of slavery continues to impact the position of Black people in American society. To understand how these differences play out on Principia’s campus, the Pilot interviewed 23 randomly selected students. They weren’t asked about their partisan affiliation, but rather these questions: How do you define racism? Do you believe systemic racism exists in the United States? Why or why not?

Initial reactions to the first question varied as much as the definitions themselves. Some reacted with enthusiasm: “I’ve actually been thinking about this a lot recently.” Others were surprised, with responses ranging from “Well, shoot,” to “Wow, I was not expecting to answer that today.” Others were just silent.

Those who did answer all brought different definitions to the table.

“[Racism] is degrading a person or group of people or a group solely based on their skin color or ethnicity or where they’re from,” says senior Mitchell Gill.

“Saying or doing things to make someone who is a different race feel inferior … on purpose or accidentally,” says junior Valerie Perse. “I don’t feel like a lot of people try to be racist, but sometimes something they say can come off that way.”

“When a person thinks that their race is superior than that of another person, in so many contexts: in the way they talk, in the way they behave, in the way they do things,” says sophomore Emmanuel Lopeyok.

While at first glance these definitions appear similar, they differ in key ways. The first definition includes ethnicity and nationality. The second identifies racism as both conscious and unconscious. And the third identifies a different power dynamic, a sense of superiority on part of the perpetrator that is communicated implicitly and explicitly.

In addition to giving their definition of racism, some students explained other definitions they have heard and the new dimensions of racism they were considering, illustrating the many definitions of racism held by different people.

“Originally, I used to think racism was just like prejudice … not fair treatment toward people based on their race,” says Sperr. “More recently I’ve heard … it’s against people that are specifically of an oppressed race, not the race in power.”

Molly Loveless, a junior, recalls hearing a similar definition that made her stop and think. “A lot of people say you can’t be racist against white people because they’re not a minority.”

In her book “So You Want to Talk About Race,” author Ijeoma Oluo explains why people’s different definitions of racism hinder productive conversations on this issue. “Probably one of the most telling signs that we have problems talking about race in America is the fact that we can’t even agree on what the definition of racism actually is,” she writes.

Like any definition, the elements included in a definition of racism affect how you see racism manifested in society, writes Oluo. If people define racism differently, they can disagree about whether or not racism exists simply because they are looking for different elements.

How you define racism also impacts whether or not you believe racism can be systemic, and in the United States, attitudes about systemic racism can also vary based on party identity.

The 2020 Pew research report shows that 49% of Americans believe the United States has not gone far enough in giving Black people equal rights with white people, while 34% believe it has been about right, and 15% say it has gone too far. The 2019 Pew study shows that 59% of Republicans believe the legacy of slavery has not much or no impact on the position of Black people in American society, while 80% of Democrats believe it has a great deal or a fair amount of continued influence.

Echoing the findings of the Pew study, Principians who believe systemic racism exists in the United States point to the legacy of slavery, income differentials between white people and people of color, discrepancies in resource allocation in education and healthcare, rates of incarceration, and differences in representation in government.

Marc Trinidad, a junior, says he believes systemic racism exists because students from the inner city would be bussed to his Boston suburb to create a diverse student body at his high school. If there wasn’t systemic racism, he says, the district would not have to bus people in to achieve diversity.

Agreeing with Trinidad, senior Sarah Ungerleider says, “Schools that serve locations where people of color live in higher amounts are often not given the same financial resources as other schools.”

While many like to believe in the American dream, “that’s just not the case when people from such a young age have fewer resources than other people,” she adds.

Junior Edner Oloo explains it differently. She recalls watching a video about vaccine distribution and the suggestion that marginalized groups should receive the vaccine first. For Oloo, Black and Hispanic communities immediately came to mind. “That shows you they’re systemically marginalized.”

Sophomore Lopeyok and freshman Ashley Kamau say systemic racism can be harder to notice unless it is your lived experience.

“There’s just … a lot of hurdles that people of color have to get through, and white people – they don’t have those kinds of hurdles,” says Kamau. “Unless you are actually a person of color it’s hard to actually understand those kinds of hardships.”

Others were less certain of whether systemic racism exists, or didn’t know how to define it. “I don’t think I’m informed enough…to have an opinion on it,” says junior Emme Schaefer.

One student, who wishes to remain anonymous because of their leadership position on campus, says they believe systemic racism exists in the United States, but not necessarily in the same way that many others believe it operates.

“Most of the systemic racism that I see or that I believe exists comes from certain economic policies [like welfare] which are intended … to help out people in disadvantaged communities,” they say. “But I think that ultimately, they end up not being beneficial in the long run and they tend to create a dependence on the government and kind of keep people from getting out of those situations and moving up and forward in life.”

Colarossi does not believe systemic racism exists because he feels that the current system allows all people to rise. “I believe there have been groups in the past who have been mistreated, but I think in a free society we work to alleviate those differences and those mistreatments of those groups.”

The differences in definitions of racism and beliefs about the existence of systemic racism of those interviewed follow national patterns. Author Oluo writes in her book that definitions of racism typically fall into two categories. In the first, racism is “any prejudice against someone because of their race.” The second definition adds, “when those views are reinforced by systems of power.”

When people talk about racism, they can be talking about two fundamentally different things: personal prejudice or personal prejudice born of social conditioning or systems. The second is more often unconscious, meaning it’s not intentionally hateful. For example, Oluo considers complacency with the status quo to be a form of racism because the status quo perpetuates inequality between white people and people of color.

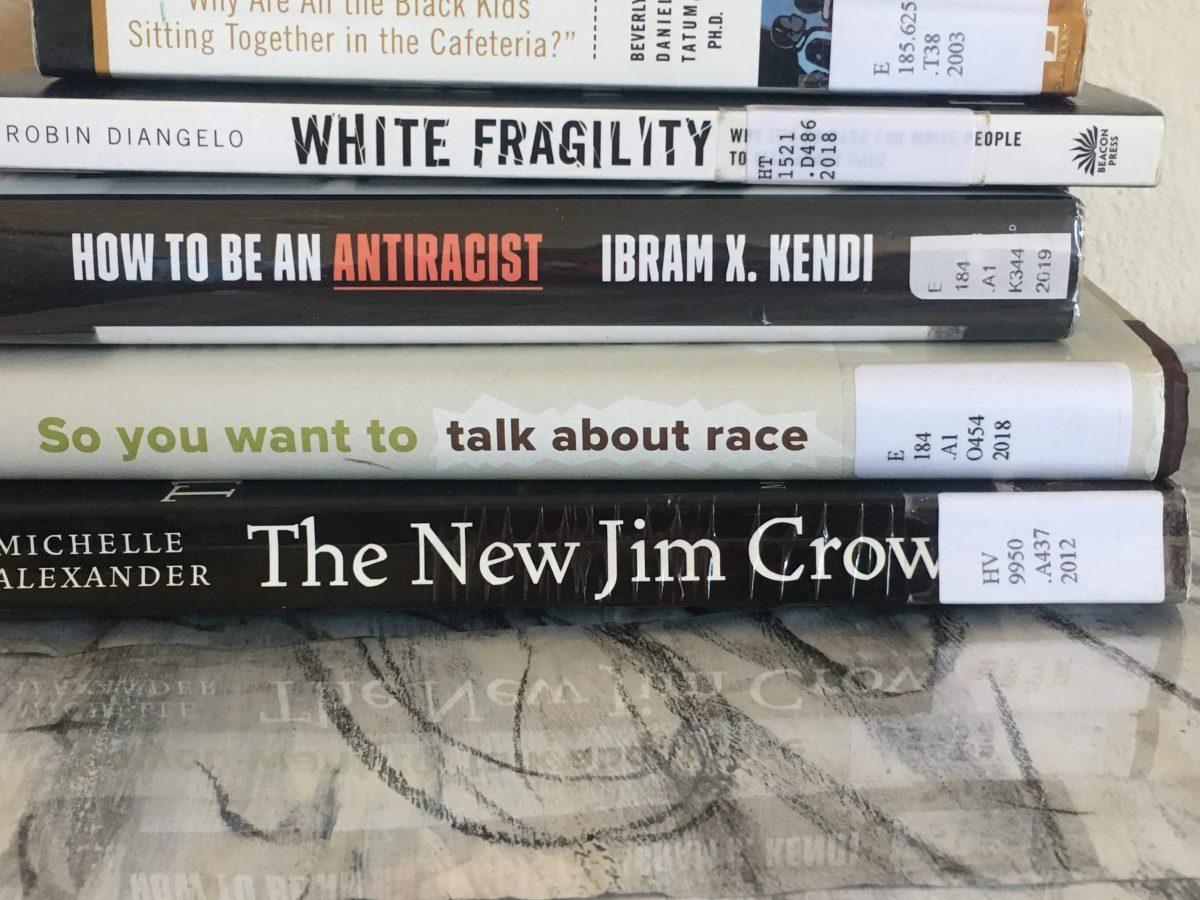

Just as race scholars Oluo, Michelle Alexander, Beverly Daniel Tatum, Robin DiAngelo, and Ibram X. Kendi all begin their books with a definition of terms, perhaps it would help to ask others: What do you mean when you talk about racism?

Authors of books exploring racism frequently present definitions of ‘race’ and other relevant terms early in their writing. But studies show that, across America, people have their own, differing definitions. Photo by Tara Adhikari.