By Tara Adhikari

When Stefania Passaglia first started attending Principia College in 2013, she had the financial support of her parents who lived and worked in Argentina. But, after her freshman year, Passaglia realized the toll tuition payments were taking on her parents because of the currency differential, and she decided to withdraw.

“The economy [in Argentina] is never doing well,” explains Passaglia, “I just didn’t want to put that burden on them. I felt like it was my responsibility.”

Five years later, in January of 2019, Passaglia returned to the College, having saved for an entire year to cover TOEFL exams, SAT exams, VISA costs, and a plane ticket to the United States. She works 20 hours a week – while taking 18 semester hours – and works 40 hours a week over summer and winter breaks. But sometimes even that doesn’t seem like enough.

“There’s aggregated pressure during the semester to not only pass and do well in school…but also excel at other things,” she says.

Passaglia describes aspirations to join the swim team, participate in student government, and work on art.

“I would love to have the time to do even one of those things,” she says, but it’s not feasible with her busy work and class schedule.

At Principia College, the international student population spans 25 countries and constitutes 21% of the student body. With so many different cultures blending together in one educational system, inclusion becomes both incredibly complex and incredibly important. The Pilot spoke with 10 international students to try to understand their daily realities – the challenges that come from being in a new country, away from home, and, for many, also entirely financially responsible for their education.

“You know you have an inclusive university if everybody in the university, across the board, can agree that it’s an inclusive university,” says Christina Yao, the Program Coordinator of the Higher Education and Student Affairs program at the University of South Carolina. Until that happens there needs to be constant questioning: “How are we more equitable in our policies and practices so that everybody can participate?”

Such conversations often involve “a deconstruction of the way that things have always been done,” she says.

One barrier to full participation for some international students is the weight of financial responsibility. Despite generous financial aid, work is a de facto reality. The average financial aid award for international students for the 2019-2020 academic year, which accounts for both need-based financial aid and scholarships, was $38,512, just $2,938 shy of the cost of tuition, room, and board. Add to that figure the cost of insurance, taxes, student fees, a phone bill, and personal expenses, estimated by the Office of Admissions to be at least $4,000 each year, and you get a reasonable picture of the cost of attendance.

Data from the Human Resources Office and Finance and Accounting Office indicates that for the spring 2020 semester, 100% of the international student population worked an average of 13 hours per week compared with just 59% of the domestic student population who worked an average of 8 hours per week.

For many international students, without financial support from parents back home, nor any other way to defer costs, work becomes as much a part of the college routine as classes, with the pressing reminder of a PrinBill deadline never far from thought.

“We’re a grateful bunch,” says sophomore Ure Okike, the International Student Representative on Student Senate from Abuja, Nigeria. “A lot of us are aware of how subsidized our education is here and we are aware of the opportunity we have.”

Time is money

Nic Kosmas from Nairobi, Kenya, explains the priority working takes in very simple terms: “We gotta pay the bills,” he says.

Missing the end-of-year PrinBill deadline would mean international students can’t enroll for another term and their visa would be cancelled. For Kosmas, there is no fallback option, no safety net of family support. While Kosmas was able to participate in junior varsity soccer for a term, varsity soccer was out of the question because of the time commitment.

“For an international student, who really has to work, it’s not like you have a choice,” he says.

Without understanding the financial weight behind scheduling choices that many international students face, it becomes easy to view this choice in very different terms. Okike recalls being told her freshman year that “you international students just don’t participate and you don’t really get involved. I wish you guys would.”

This type of participation involves not just time and finances, it also requires a degree of comfort and confidence in the American cultural environment. Sammy Keller, a senior from Hamburg, Germany, began attending the Upper School as a sophomore. He describes himself then as “very shy” and “very quiet,” descriptors that no longer fit him as the current president of Lowery House, known for midnight fireworks and elaborate pranks.

It took time for Keller to acclimate enough to run for a position like house president.

“I think the reason that my outlook changed so much and that I was able to be so much more outgoing is that I had the three years that I was at the [Principia] Upper School to try to get the hang of American culture,” he says.

Despite the similarities between the United States and Germany, coming here is “a culture shock, no matter where you come from,” Keller says.

Alessandro Chavez, who came to Principia College after just one year of learning English in Lima, Peru, describes a similar experience as Keller, feeling intimidated to speak up in class, and afraid that what he had to say wouldn’t sound as smart.

“I am a senior now and I have more trust in myself and I trust people more and I trust my teachers more so that has changed me,” he says. “It’s all about trust.”

Visualize trust and belonging as a series of concentric circles, says Yao, whose research focuses on international education. It starts in your own community, with the people who understand you best, and expands outward. For many international students, that inner circle consists of other international students, and expansion outward happens gradually through exposure. Yet, “there also needs to be effort on part of U.S. students to reach out a little bit,” says Yao.

A juggling act

In the 2019-2020 school year 31% of the international student community (21 students) participated in athletics, while 45% of the domestic student population (157 students) did the same. In all, international students comprised 12% of student athletes.

Currently, there is one international student serving on Student Senate, two international students serving as house presidents, one international student on the Public Affairs Conference Board, seven international students on the International Perspectives Conference Board, no international students on the CSO board, and two international students writing for the Pilot.

For those international students who do find a way to get involved in extracurricular activities, it resembles a carefully planned juggling act. George Agai, a four-year varsity soccer athlete from Nairobi, Kenya, learned to balance 18 hours of work per week with the competition season. He attributes this both to the work ethic he honed on the soccer field and to time management skills.

Camille Abadie, a softball and swim athlete from Pau, France, who has also served on house board and participated in the videography club, works 10-12 hours per week during the semester and pulls from her savings account to cover the rest of her PrinBill.

Desmar Ngei, a former student from Nairobi, Kenya, played on the women’s soccer team her freshman year but describes the balance with work as, “hard, very hard.” Building her work schedule around soccer practice meant taking work shifts at night that went until 1 a.m.

“It’s class, and work, and that’s just how you have to function,” she says.

So why even bother to get involved in extracurricular activities?

“Research shows that involvement both in and out of the classroom are beneficial to all students because involvement may help develop leadership skills, increase campus engagement, and overall remain more invested in the college experience,” explains Yao, of the University of South Carolina. “Engaging with organizations and events will benefit international students in learning more about the culture of their college and meet more people beyond their initial network.”

The students interviewed described extracurricular activities as a stress outlet and a place for community building and interaction.

“Playing with my best friends, there’s nothing more enjoyable than that,” says Agai.

Making it work

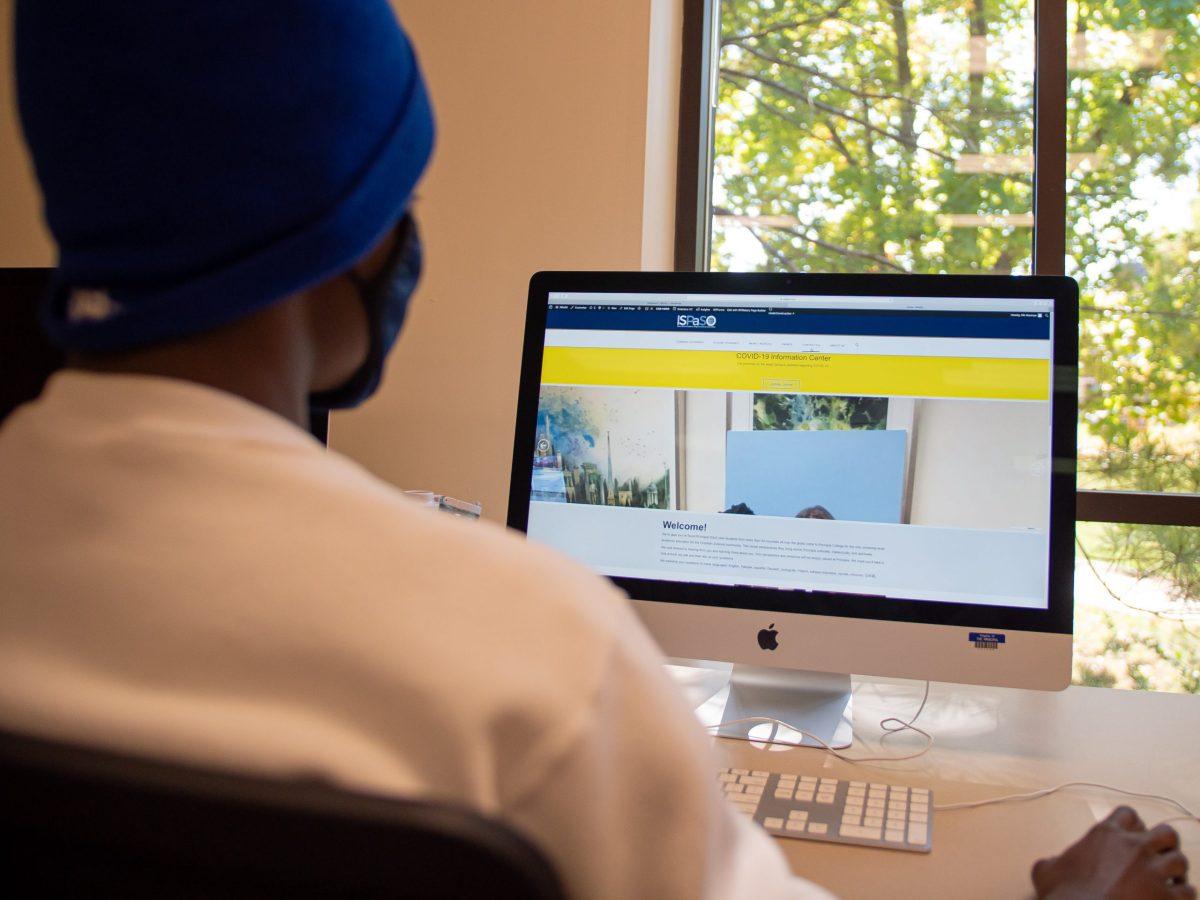

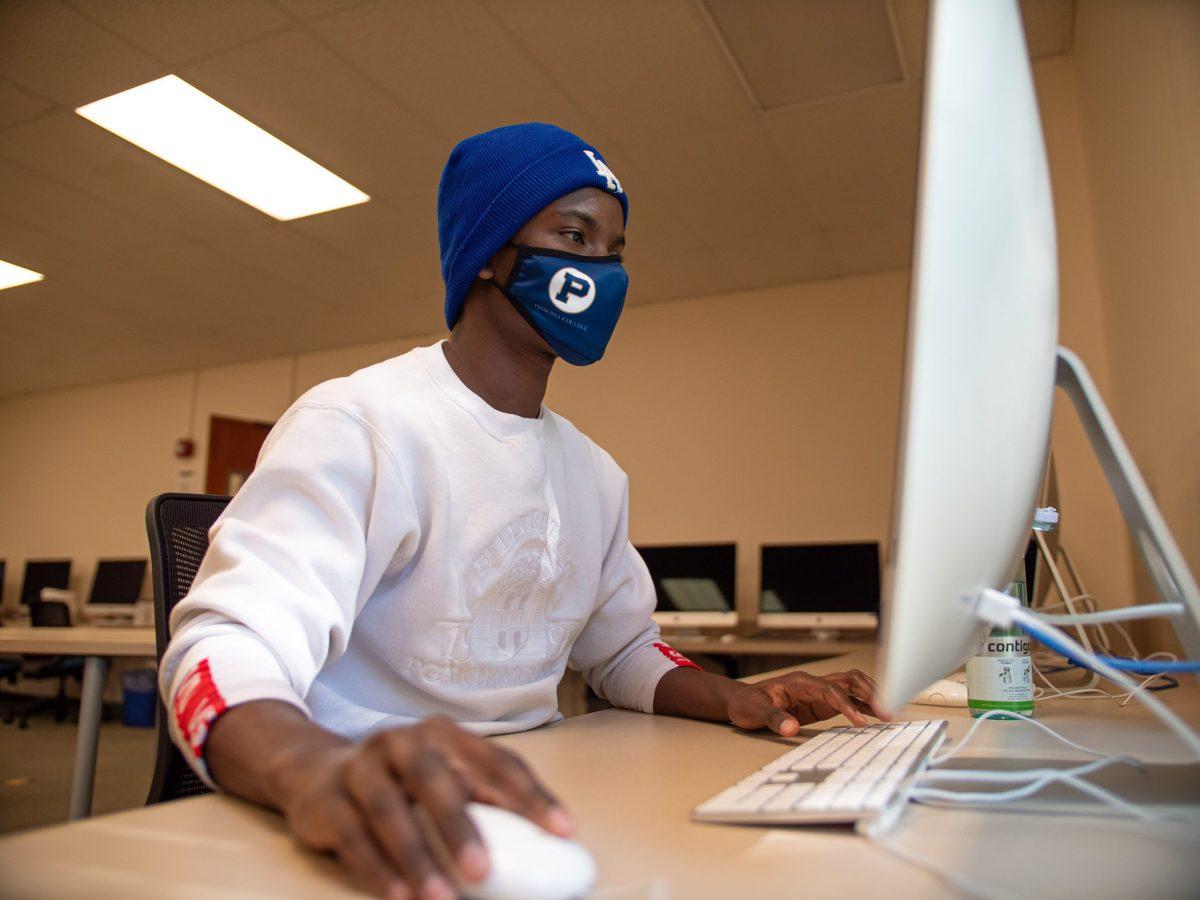

Despite the challenges that come from 20-40 hours of work per week, there are models of work experience that directly benefit international students in their professional development. This semester, Kosmas is working 12 of his 20 hours in the International Programs and Services Offices designing and building a website from scratch for international students with information on visa statuses, among other things.

“It’s professional development for me,” he says. “It relates with my major as a computer science student.”

As part of this job, Kosmas meets with David Njau, director of the office, and the other international student workers to discuss how they can use the website to benefit the international student community. Ideas they’ve generated include providing resources for career development specifically for international students and featuring international Principia alumni so that current international students can start to envision the opportunities available to them.

“I feel like this is something bigger than just my own personal growth,” Kosmas says. “I feel like this is something maybe 10 years from now we look at and [will] be like, ‘wow, we are glad we started this.’”

When asked to become a student manager in Dining Services, Keller, the house president of Lowrey, began to think of himself as a leader. That led him to take on other jobs that tapped into this ability, working as a residential assistant, a visiting weekend ambassador, and a social assistant. Now as house president, when asked to make nominations, he thinks first of international students like himself who have untapped leadership potential, and recommends that others do the same: “Try to think more international,” he says.

And to international students, he adds, “just because English isn’t your first language doesn’t mean you can’t be a house president.”

Inclusion is not a one dimensional concept. On a policy and program design level, it involves understanding the very real barriers, both cultural and financial, international students face in a domestically-oriented institution. On an individual and social level, inclusion requires compassion and outreach, as Ngei points out.

“I would just love people to be more understanding of international students and you know take the time to know them and try to connect with them,” she says. “I think that would mean a lot to a lot of people, to be able to feel like they have a family away from home.”

In featured photo, Nic Kosmas, a senior, works 20 hours a week – 12 of which he spend designing and building a website for the International Programs and Services Office with information on visa statuses, among other things. Photo by John Woodall.