By Tara Adhikari

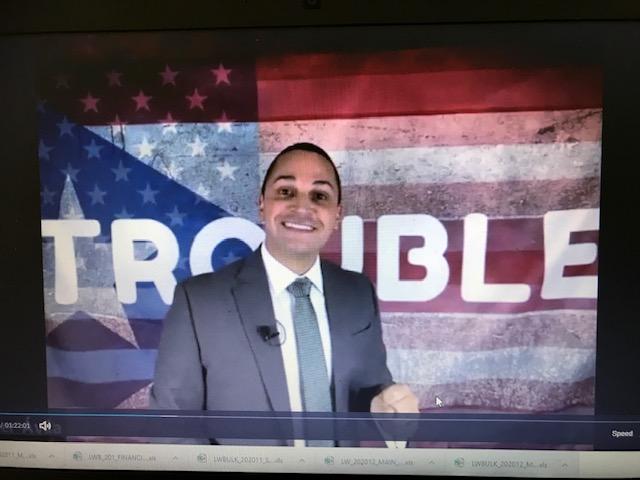

“How’s it possible for me to be white one day, brown the next day, and exactly the same person with the same value and values?” asks Javier Ávila as he stands in front of a blended American and Puerto Rican flag Zoom background with the word ‘Trouble’ spelled out in white block letters. The long answer? Move from Puerto Rico to Pennsylvania, marry a white woman, and have a “whitino” child. The short answer? The fallacy of race.

In his comedic one-man show, The Trouble With My Name, professor, author, and poet Javier Ávila explains the American Latino experience and what it’s like to become a minority. Over 100 Principians tuned into the show, which was scheduled in celebration of National Hispanic Heritage Month and broadcast over Zoom on October 3 with watch parties sprinkled across the campus. Covering everything from home remedies to military service to the awkwardness of being corrected on how to pronounce your own name, Ávila brought together the seriousness of racial prejudice and need for cultural awareness with the lightness of laughter.

After spending 31 years in Puerto Rico, Ávila moved to Pennsylvania, experiencing minority status for the first time. “One of the burdens of that is that you constantly have to prove to the majority that you are not the stereotype that they have of you. And my friends, that can be exhausting.”

“Sometimes you just want to take off the mask and be invisible in a positive way, but you can’t,” says Ávila, because you automatically stand out for the color of your skin, or even for your name.

When moving into his house in Pennsylvania, Ávila was outside trimming the rose bushes when his neighbor walked over to introduce himself. “Growing up in Puerto Rico I learned that [in the United States] when people move into a new neighborhood, their neighbors get them apple pie.”

When Ávila’s neighbor climbed out of his car, dressed head to toe in golf attire, Ávila excitedly awaited the standard pie delivery. But when they shook hands the neighbor instead asked him about the price of his landscaping services. “We both thought something different of each other,” says Ávila.

Whether it is being told to speak “American” and “go back to your country” when eating at a restaurant or being asked for lawn quotes, when confronted with instances of prejudice, Ávila channels his anger into poetry. Each segment in the show was structured around one of these poems.

“I’ve seen the show twice and the first time I saw it…I cried,” says Assistant Professor in the Languages and Cultures Department, Annabelle Marquez, also from Puerto Rico. “I cried because I heard some of the things that I have lived.”

The first poem Ávila read, titled ‘Denied Service,’ reminded Marquez of her father who served as a U.S. Marine in the Korean War. When her father passed, he requested the American flag, not the Puerto Rican flag, on his casket. “He said being in the U.S. military was the best thing that ever happened to him. He was so proud of representing the United States of America.”

Yet, as Ávila brings out in his poem, despite this long record of military service and sacrifice, Puerto Ricans in the U.S. continue to be treated as outsiders.

In the bit that gave the show its name, Ávila talks about the challenges of having a name that nobody can pronounce. Even Siri gets it wrong, calling him “heavier.” Senior Sarah Ungerleider immediately found the similarity with her own experience. “My last name [is] 11 letters long [and] always gets mispronounced. The worst was in first grade – my principal called me over the loudspeaker Sarah Ugly-leader.”

While she could relate to the name mispronunciation, Ungerleider recognizes how, as a white woman, she escapes other racial and cultural prejudices which Ávila has experienced.

Senior Chuy De La Cruz says the parts of the show where Ávila talks about his Grandmother’s cooking and the fix-all remedies of Witch Hazel and Vicks Vaporub – that can treat everything from a pimple to the flu – and even just hearing Ávila speak Spanish brings “a sense of home.”

“I really liked that he gave us a sense of courage,” says senior Brandon Robles Martinez, noting that many of Ávila’s experiences resonate with his own. When sitting in a Midwest restaurant, Martinez has noticed service diminish when he switches to Spanish to converse with a friend. “I used to get kind of upset about it. They had no reason to change their attitude.”

Hearing Ávila’s comedic take on these instances of prejudice helps Martinez lose some of that anger and see that he does not have to take it personally. Yet, taking responsibility for greater intercultural competence rests on everyone. “[The U.S.] is the melting pot of a lot of cultures and people should be open to other cultures.”

As Ávila explains, “I’m building a cathedral of equity. This means that we’re working on something that is much larger than we are, but we must do our part.”

Javier Ávila performs his one-man show over Zoom on October 2, 2020. Around 100 Principians tuned in. Image courtesy of Heather Holmes.